Hans Boersma on Secondary Action and the Primacy of Contemplation in Mark 9:14–29

We are grateful to the Messiah University Honor Program and to author Hans Boersma (his many books include Heavenly Participation, Scripture as Real Presence, and Seeing God: The Beatific Vision in Christian Tradition) for permission to share the audio and text from this chapel talk given at the Brubaker Auditorium on October 5, 2021. Dr. Boersma reflects on Mark 9:14-29, contrasting and comparing Jesus’s action (healing the demon-possessed boy) with the contemplation of Christ’s transfiguration in the immediately preceding narrative, and arguing that it is contemplation, not action, that is primary.

Audio

“Secondary Action” with Hans Boersma (delivered October 5, 2021 at Brubaker Auditorium, Messiah University)

Lecture Text

You and I, we are activists. We are moralists. We are a nation of do-gooders. We love to help out. And when people don’t think they need the help we offer, well, we’ll change their minds. For there’s nothing more important than turning the world into a better place. You haven’t really done anything until you’ve been on a missions trip. You’ve haven’t truly cared until you’ve called out for justice. Add your own example. No matter what shape or form it takes, in today’s world, it is action that matters. It’s what you do that ultimately counts.

I have one purpose this morning: I want to try and show you that action is not first and foremost. Biblically speaking, it’s not what we do that is ultimate, it’s what we see. It’s not action that’s primary, it’s contemplation. We could turn to many different biblical places to make this point. We could compare Mary and Martha. As you know, Martha is busy, while Mary is sitting at Jesus’s feet; Jesus seems to think that Mary has chosen the better part. Or think of Leah and Rachel. Leah is busy: every year another little one is sitting on her lap. Rachel, by contrast, is barren. Leah stands for the active life, Rachel for the contemplative life. But, Leah’s eyes do not sparkle. It is Rachel’s eyes that capture Jacob’s heart. Or, finally, take Peter and John. Peter is always on the go. “I’m off fishing,” says Peter, right after Jesus’s resurrection. If Jesus has died, then Peter isn’t hanging around. He’s got things to do. But John, well, he is different. He reclines at table at the bosom of Jesus, taking in his master’s mystical words. And you know: John is the disciple whom Jesus loved. We could compare Martha and Mary; Leah and Rachel; Peter and John.

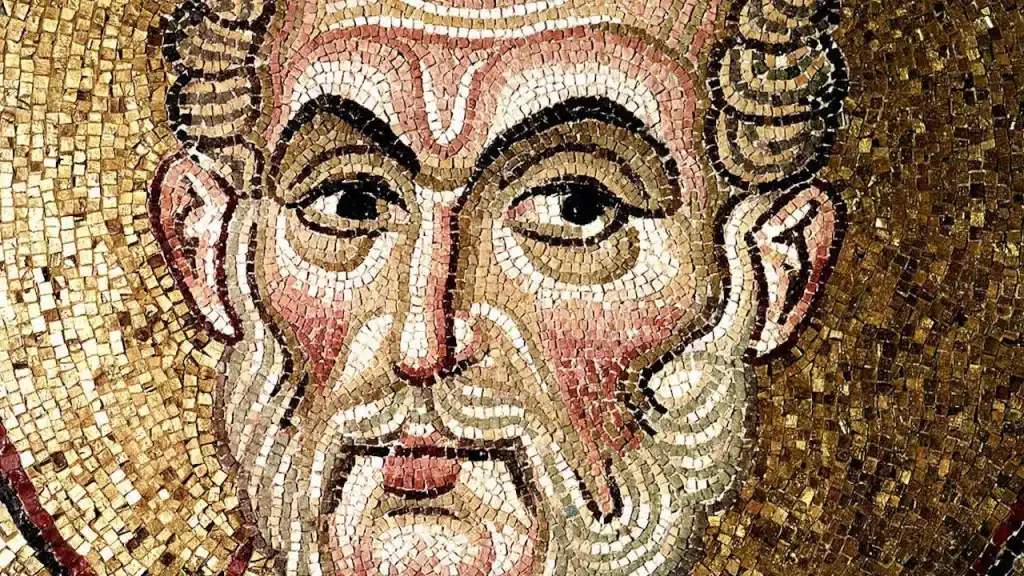

But I want to go somewhere else with you this morning. I want to go to the foot of the mountain in Mark chapter 9. It is a moment of greatest distress and anguish. The spirit had screamed aloud; the boy was violently tossed to the ground, his mouth foaming, his teeth grinding away; his body had convulsed and writhed; and had then turned rigid. Everybody thinks the boy is dead. This is the moment of no return. This is where it all ends. Most of them said, “He is dead” (Mark 9:26). But then: “Jesus took him by the hand; lifted him up; and he arose” (9:27). An astounding moment of action. Jesus is doing something. He is changing the world. This is where action happens—despair gives way to hope; death makes room for life; grief turns into joy. All because Jesus took him by the hand.

I imagine being the boy’s father. I tried bringing him to Jesus. But it was not to be; for Jesus was gone, up on the mountain, with three of his disciples, one of them (Peter again) so caught up in his vision that when he saw Jesus transfigured, he suggested they set up tents. Meanwhile, where I was, at the bottom of the mountain, the disciples were unable to help. They gave no thought to my pain, my fear, my anguish and distress. Instead, they let themselves be baited into a theological argument with scribes who taunted them for being unable to heal my son. We (my son and I) were left standing on the side.

That’s how it began. But it all changed when Jesus, who had just shown Peter, James, and John his resurrection light—his clothes radiant, intensely white, as no one on earth could bleach them (9:3)—came down, heard the vehement debate, and then saw me, as I stepped forward and offered him my prayer: “Teacher, I brought my son to you.” Then, after I had some back and forth with Jesus, he took my boy by the hand and pretty much literally raised him from the dead.

How did this father react to the healing of his son? The amazing thing is: we don’t know. Mark doesn’t tell us—at all. It’s as though the father’s reaction is utterly inconsequential. There’s not a word about his thoughts, emotions, expressions—nothing at all. Instead, as soon as the boy is healed, Mark’s lens zooms away from the intimate scene of Jesus taking the boy by the hand and lifting him up to an in-house, private setting with the disciples: “Lord, why could we not cast it out?”

Why is it that Mark turns our attention away from the dad, as if completely forgetting his tears and affliction, his distress and anguish; and asks us instead to focus on the disciples and their “Lord, why could we not cast it out?” The reason is a simple and straightforward one—though it may not be a pleasant one for us to hear. At the very end of this story the disciples and their question take centre stage, because at this point it is you and I and our question that take centre stage. “Lord, why could we not cast it out?” This is not only the disciples’ question; it is yours and mine. Why is it you and I can’t do the things that Jesus does? That is the question that dominates the story from beginning to end. That’s what the theological argument with the scribes was all about. That’s what the boy’s father reported to Jesus: “They were not able,” he says in verse18. So, now that Jesus has done what they could not, now that the boy has been healed good and proper, it is time to resolve the theological debate: “Why could we not cast it out?”

My hunch is: the father knows the answer. He knows why it is that Jesus was able to do what the disciples were not. How does he know? Let’s think a bit more deeply about this man, about who he is. He doesn’t have a name. He is “one of the crowd.” Perhaps the saddest part of this story is not even the boy being tormented by this unclean spirit. Perhaps it is instead the disciples and scribes arguing about why it is the disciples cannot exorcise the spirit. They are having an abstract argument while the boy and his father are standing on the side, left in the cold, in the heat of the argument. “O faithless generation!” This is Jesus’ commentary, both about the scribes and about the disciples. “O faithless generation!” It is a fearful denunciation, but deserved because the disciples and scribes alike fail to grasp what life with God is all about. They fail to see that people are broken and hurt.

Remember when Jesus fed the hungry crowds in chapter 6? “He saw a great crowd, and he had compassion on them, because they were like sheep without a shepherd” (6:34). The same in chapter 8—again, there is nothing to eat: “I have compassion on the crowd,” says Jesus (8:2). In our passage, “one of the crowd” shows up at the foot of the mountain, and he offers up a prayer to Jesus—9:23: “If you can do anything, have compassion on us and help us.” This is a stunning moment. No, I know, his prayer is not perfect, because his faith is not perfect. Jesus even chides him, “If you can! All things are possible for one who believes” (8:23). The man himself recognizes the weakness of his faith: “I believe; help my unbelief” (8:24). And yet, we must pause at this amazing prayer, “If you can do anything, have compassion on us and help us.” This man, “one of the crowd,” knows he and his boy, they need compassion. Only compassion is able to help. They need someone to take them by the hand. What they need is someone to act.

The disciples have lost themselves in an abstract debate with the scribes about why it is that they could not cast out the evil spirit. It’s not that the question is wrong. “Why could we not cast it out?” is a vital question to ask. It’s just that they’re unable to answer it because they don’t recognize that it can be answered only by looking for the character of God.

The boy’s father, though his prayer is clumsy and his faith is weak, from the outset recognizes what it takes to heal his boy: “If you can do anything, have compassion on us.” It is precisely because he has been brought so low, because he is suffering distress and anguish, that he knows with the Psalmist: only God’s compassion, only God’s mercy is able to deliver his boy, to loosen his bonds (Ps 116:8, 16). The reason the disciples cannot cast out the spirit is they lack the character of Jesus. They are like the people James chastises for mistreating the poor. He warns them to have mercy: “Mercy,” says James, “triumphs over judgment” (Jas. 2:13). Mercy, compassion, speaks of the heart of who God is. God, you could almost say, speaking reverently, feels in his gut compassion for “one the crowds,” for James’s guy with “shabby clothing,” for the boy writhing on the ground. Compassion is his name.

The two stories are side by side in Mark 9—first the story of transfiguration: Jesus on top of the mountain, transfigured before the three disciples, his clothes radiant, intensely white, as no one on earth could bleach them” (9:3). Then the story of Jesus healing the boy with the unclean spirit. And the puzzling question it raises for the disciples and for us, is: “Why could we not cast it out?” The two stories are like Mary and Martha, like Leah and Rachel, like Peter and John. Contemplation happens on top of the mountain, action at the bottom of the mountain.

Moses, you remember from the Book of Exodus, was on top of the mountain. There he shines with the glory of God’s compassion. The Lord passes by him, and proclaims his name, “The Lord, the Lord, a God merciful and gracious, slow to anger and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness” (Exod. 34:6). When Moses comes down Mount Sinai, his face is still shining with glory, his ears are still ringing with mercy. God’s glory is his mercy, his compassion. When Jesus comes down the Mount of Transfiguration, he too comes with the glory and mercy of God. Jesus is able to help because his name is the mercy of God; because his very dwelling place is the Mount of Transfiguration. The disciples can’t help because, well, because they’re lacking the mercy of God; they have not spent time on the mountain with God.

There’s nothing wrong with being active. Jesus was active. He’s the one that casts out the boy’s demon. It’s not that action is wrong. It’s just that action is second. You first need to be on the mountain. Only then can you come down and do things. Believers are people who are either going up the mountain (in contemplation) or are coming down the mountain (in action). Jesus tells us plainly: “This kind cannot be driven out by anything but prayer” (Mark 9:29)—only if our face still shines with the presence of God can we do the acts of the mercy of God. The father’s prayer to Jesus may be a bumbling prayer (“If you can do anything, have compassion on us…”), and his faith may be a wavering faith (“I believe; help my unbelief”). But Jesus hears his prayer and sees his faith. And so out of the depth of his divine compassion, Jesus rekindles hope, restores life, and renews joy.

Saint Mark doesn’t tell us the father’s reaction to his son’s healing. But if it’s true the dad has just seen something of the glory of the transfigured Lord; if it’s true he himself has been touched and changed by the mercy of God; if it’s true that he has seen Jesus take his son by the hand and lift him up—then I imagine he must have burst out in song with Psalm 116

I love the Lord, because he has heard

my voice and my pleas for mercy

The snares of death encompassed me;

the pangs of Sheol laid hold on me;

I suffered distress and anguish.

Then I called on the name of the Lord:

“O Lord, I pray, deliver my soul!

Gracious is the Lord, and righteous;

our God is merciful.

The Lord preserves the simple;

when I was brought low, he saved me.

Return, O my soul, to your rest;

for the Lord has dealt bountifully with you.

Friends, I know you want to be the hand of Jesus—taking the boy and lifting him up. I’m not against action. I’m certainly not against compassionate healing. The only question is: Will you be able to heal? For true action is possible only for those who first have contemplated the glory of Jesus.

Books by Dr. Hans Boersma

Review these Related Courses

Scholé (Restful) Learning with Dr. Christopher Perrin helps educators to more deeply understand and apply the tradition of contemplation and restful learning encompassed by the word scholé.

Teaching the Bible Classically with Dr. Fred Putnam provides a pedagogy for teaching the Bible as a classic text. This course is also offered as a graduate course for graduate credit through a partnership with the Templeton Honors College.

Try ClassicalU free for 14-days!

Note: you can also find related reading on this topic of the fourfold sense of scripture (that Dr. Boersma treats at length within his book Scripture as Real Presence) in other online locations such as this review by Craig A. Carter of the book Interpreting Scripture with the Great Tradition: Recovering the Genius of Premodern Exegesis or this brief article “Unlike Any Other Book” by Hans Boersma.

Responses